- Home

- Beat Sterchi

Cow Page 6

Cow Read online

Page 6

He was a rough diamond, the manager of the cooperative. Big-bodied, heavy-headed, slightly flat-footed and occasionally shaven-necked and even shaven-templed. In the village he was thought of as a likeable man, but he was sizing up Ambrosio with an insolent expression, as though he were a calf on special offer. Top to bottom. He circled him twice, sidling and staring, with the load still on his shoulders. He examined him, feet, legs, hands, shoulders. From front and behind. Pero que tiene este hombre? thought Ambrosio, staring fixedly at the furthest corner of the room. The manager laughed. ‘What did you say?’ he turned to Knuchel. ‘Needs some proper trousers, an overall, boots and a cap? You want him kitted out then. I’m not sure, Hans, I don’t know if we’ve got anything his size in stock. There’s not very much of him, is there?’

‘Well, come on then, let’s try something on him, show me a pair of your good trousers.’ Knuchel went on ahead. In the shop part of the cooperative there was a smell of leather, hemp and feedstuff. A cow was laughing happily on a poster. PROVIMIN it said on top in big letters, Protein, Vitamins, Minerals in smaller letters below. Fertilizer, seeds, salt, machine oil, paint, chicken feed, were all heaped up in plump sacks and in buckets and cans. Equipment dangled from the walls and ceiling: spades, rakes, potato drills, baskets for stones, sickles and scythes, feed measures, hoes, axes, whips, cleavers, sledgehammers, a couple of small chainsaws, weedkiller sprayers in the finest brass, in all sizes, next to them in a corner, hand-forged crowbars, some rolls of barbed wire, and all over the place leather gear, plough-chains, halters, calf ropes, spring-hooks, straw binders, all of it dry, bright, clean and waiting, all untarnished and pristine, with red, blue or gold manufacturer’s labels and trade marks on it; and all ‘extra tough’, ‘extremely durable’, ‘hand-tooled’, ‘indestructible’, ‘quality’, ‘guaranteed for ten years’.

Knuchel pointed up at a shelf with neatly folded work clothes. ‘There,’ he said, ‘you’ve got all we need.’

‘Goodness,’ exclaimed the cooperative manager. ‘So you’re proposing to get him quality stuff, and in the green too!’

‘Well, yes,’ said Knuchel, ‘as I was saying to the cheeser, the fellow knows how to milk, he’s got a feel for it. Doesn’t speak a word of German, but you never have to tell him anything twice. And he’s careful with it, like a glassblower, I don’t mind investing in a set of good clothes for him.’

The co-op manager put his sack of milk powder down on the floor, loosened his shoulders, and took out the red pencil he kept behind his right ear. It was a CARAN D’ACHE, medium hardness, with which in the course of time he’d acquired the reputation for being a considerable ready reckoner, even beyond the boundaries of the parish. Co-op manager and pencil went together, they were inseparable. Nimbly they added, subtracted, multiplied and divided, everywhere on demand. They made their science accessible to everyone, in the Ox, in the shooting booth, at the school committee, at the fire brigade meeting, at choir practice, when milk accounts were drawn up, before the sermon, after the sermon, the co-op manager always had his well-sharpened red pencil behind his ear. Anyone who needed help with figures, percentages, rates of interest or taxation, turned to him. There were few disappointed clients, the red pencil worked fast and accurately. The figures were written down wherever: in the margin of the Official Journal, on a beer mat, on a wooden wall, on a cigarette packet, in the back of the hymn book, even, in the course of conversation in a field, when there was nothing else available, on the palm of his left hand. There was hardly a single calf or cow in the Innerwald area whose diet hadn’t been determined by the co-op manager with his red pencil. He knew how many litres of carbolineum Farmer Hubei needed for his barn and machine shed to get rid of the woodworm without poisoning the cattle. It was he who worked out how many vitamins the old and young village bull got mixed in with their feed. It was he who was responsible for the ratio of seed and fertilizer, in short he did half the village’s sums.

Only Knuchel wasn’t overly impressed by the red pencil.

‘What do you want that for?’ he said. ‘We’ve got nothing here that needs calculating.’ He stared at the co-op manager’s hand, as though it held a revolver.

‘I’m not sure, Hans,’ the co-op manager said falteringly, scratching his neck with the tip of his pencil. ‘There’s the milk powder,’ he said in explanation. Then, again, struggling for words, ‘It’s... it’s for... you know, if everyone... we don’t go about it like that. That green-grey material is so durable, and the special cut of it, the pockets, the army buttons all double-sewed... what about everyone else? What would the farmers in the village say? Couldn’t you...? I mean, what about blue instead? Try blue. If the Spaniard stays here a year or more, then you can always still buy him the green—’

‘Damn it!’ Knuchel interrupted the co-op manager. ‘Is he a milker or a garage mechanic? I’ve told you he’s up to the work, so no one in the highlands need feel ashamed to have him milking our cows. No, my mind’s made up. I’m having green!’

‘Well, it’s up to you. Whatever you say, never said a word,’ the co-op manager replied.

It didn’t take long to try the things on.

Even the smallest of the boots were too big, the shortest trousers too long, and the smallest milking overall had sleeves that flapped round Ambrosio’s elbows. The cap covered his ears. Knuchel and the co-op manager got down on their knees. They each rolled up a trouser leg. The green-grey material was sturdy and stiff. Ambrosio hitched the waistband up to his chest. He could feel the tough seams. All double-stitching.

The red pencil totted up the prices on the sack of powdered milk. Knuchel asked for a leather strap for a belt to be thrown in too.

‘Sixty-three twenty,’ said the cooperative manager.

Swimming rather than walking in his great boots, Ambrosio plodded out. Qué país! Qué estoy haciendo por aquí? The dog Prince yawned. He sniffed at the green-grey farmer’s cloth.

‘Well, we’re off then. Thanks!’ Knuchel put his wallet back in his pocket. ‘We’ve still got to call on the mayor on account of the voles. The bloody things have got it in for me. And the moles this year, they’re like sand on the beach too. Well, so long, manager.’

The pencil went back behind his ear. Two arms thrust out, sleeves slid back over wrists, two hands aimed, ten fingers linked, grasped each other fleshily, massively, and squeezed one another hard. ‘So long, Hans,’ said the co-op manager.

Back in the village square, Knuchel shook his head. There were cowpats on the cobbles round the fountain in front of the Ox. Knuchel pointed out each one individually, and laughed sardonically. Ambrosio laughed back.

The mayor was at the back of his yard washing his milking gear. The brush in his hand pounded against pails and basins. ‘How are you doing?’ he asked Knuchel by way of greeting.

‘Oh, can’t complain,’ he replied.

‘What about your prize cow? Is she freshened yet?’

‘Already been. Another bloody bull calf. But the Spaniard has arrived. He got here yesterday on the last bus, he’s all right. I think we got lucky with him,’ Knuchel replied.

‘Don’t take it so badly,’ said the mayor, ‘every time you have a bull calf in your shed it’s as though you wanted it drowned in the fire pond. Really! You could get a packet of money for him as a stud animal. They’re looking for bulls out of dams like yours.’

‘Well, you know it’s not the way I operate, they were after me the last time it happened, as though it was the Golden Calf. I’d rather fatten it up myself and let Schindler have it. We’ve got enough milk, and the kids will feed it until it’s fit to burst. That way I’ll pick up at least a thousand on it.’

The mayor dropped the brush in the water, and the last basin clattered to the ground. ‘But Hans, you know, the AI Centre will give you fifty times that for a good bull. Whether you like it or not. Recently they bought a prize-winning Brown Swiss. He was just three years old. You could have built yourself a house with what they paid for him

.’

‘Well, there’s artificial insemination and all that, but it’s not my idea of how to go about it. Do you really believe you get healthy calves that way? I’m not so sure. And you wouldn’t catch me drinking the milk of an artificially inseminated cow, not me, no thank you!’

‘Fair enough,’ laughed the mayor. ‘But on the other hand, it’s artificial insemination that helps us with breeding. The best to the best. You can’t do any better than that!’

‘But not that way, not like that!’ Knuchel replied. ‘Sperm out of plastic bags. Deep-frozen if you please. Where’s it all going to lead?’

‘You know, Hans, I think time’s up for the summering multipurpose cow anyway. The way they’re breeding them now is different. Who’s interested if a cow’s got a straight back nowadays or even horns. Milk is what they’re after! Milk! By the bathtubful! And they’re not to eat too much, leastwise not the expensive stuff. Never mind if a cow’s got an udder like a flabby bagpipe, with tits like thorns with warts on and all, who cares. Main thing is she’s got to give more milk than the competition. You wait! Your Ruedi’s growing up. He’ll be on at you one day. In agricultural college they do all their milking with pen and paper. No one’s going to boast about a high milk yield before he’s worked out how much he’s shelling out for his PROVIMIN.’

‘Oh no, Ruedi’s not just bothered about making money. He minds about the land too. And the animals in the shed—’

‘Yes, until it’s time for him to get married,’ interrupted the mayor. ‘You think he’ll still be living under one roof with his cows. The kind of bedroom where you can hear them in their straw, and you wake up whenever one of them is wheezing a bit. You wait! These days it’s the young people who are moving out into the granny flats. It’s not like it used to be. You know, in America, they don’t even let cows like yours give birth. They get them multiply impregnated, and then they cut the fetuses out of their bellies and implant them in the uterus of inferior animals who bear them. You know what that’s called?’

‘Madness,’ muttered Knuchel.

‘They call them receiver cows! Receiver cows, that’s right!’ laughed the mayor.

Knuchel scratched under his chin. ‘America, America, the whole time. What kind of bloody racket is that anyway? Let them, who cares. We’re all right here. Our byres were blessed before they even knew what a cow was. And the way they have them looking over there and all. Not one with a proper horn on her head, all bags of bones, and udders like a score of wasps had stung them. And what they yield is 99 per cent water, it’s the thinnest milk in the world! They have to get all their decent cheese from us, that’s what the Boden farmer says, and he was over there, with his brother-in-law in Oklahoma. They haven’t got any farms like ours over there yet. That’s for sure. But I’ve got to go, my Spaniard is waiting outside.’

The mayor was still laughing. ‘All right, go on then.’

Knuchel stopped in front of the door of the cowshed. ‘Oh, one other thing. Would you send the vole-catcher out as far as the wood some time? I’ll make it worth his while. They’re raising hell under the soil.’

‘Right you are,’ said the mayor. ‘By the way, there are still a few formalities to go through with your Spaniard. I need his papers.’

‘You need his papers, eh? Anyone would think I was trying to sell a steer or something. But you know the rules. At least he’s not the first. It’ll have been the same with the Italian.’

The mayor held out his hand to Ambrosio in front of the house. Ambrosio shook it. The mayor took his cap off and said, ‘Grüß Gott.’

Ambrosio nodded, ‘Buenos días.’

‘So, you want to work over here?’ asked the mayor.

‘Sí, sí, mucho gusto.’

‘That’s fine then. You know we could use a bit of help, we’re not short of work up here on the highlands. Touch wood.’ Laughingly he tapped the milk-cart with his fingertips.

‘Right, we’re off then,’ said Knuchel. Prince shook his way back into his harness. There was a strap that had slipped from his chest while he’d been sitting, and a rope had got between his hindlegs.

After a couple of steps, Knuchel stopped the cart again. ‘I would have liked a cow calf of Blösch’s. You know, she milks so easily and that. It’s not that I’ve got anything against her at all. But what can you do? That’s the way it is! Maybe she’ll have one next spring.’ Farmer Knuchel got down to pick up the shafts again.

The mayor had stopped as well. ‘You could give the new bull a go. Who knows what the reason for it is?’

‘That’s what the wife thinks too. She’s all in favour of Pestalozzi. But I still back Gotthelf. Well, I’m off...’ Knuchel set off anew, but turned around one more time.

‘No, you can’t blame it on the bull. Nor the cow either. I don’t know myself what it is, the devil’s to blame. But it’s not Gotthelf’s fault. He always was good for my shed. Good stock, and he’s just getting to be the right age, ha! But I’ve got to go, there’s a lot still to do. Cheerio then, mayor.’

‘Think it over, will you? I’ll make you an offer for your calf myself. Say 3,000...’

Knuchel made a gesture of refusal, raising his right shoulder as though to protect his head, and then he grabbed both shafts of the cart. ‘Now I really am going,’ he said.

*

Blow upon blow. Iron onto wood and wood into the ground. The hammer whistled down again. The post trembled. Knuchel’s earth was harder than it looked. The farmer raised his hands high above his head, ten, fifteen times before another post was rammed firmly into the ground. The sound drummed back from the wood in echoes.

It was Ambrosio who held the posts. As soon as one had bitten into the ground enough to take Knuchel’s hammer blows, he went to get the next one. They were hazel posts, first-class material for fencing. The trees had been individually picked, and then dragged down the logging path. For several days in December the chainsaw had screamed, and after each load the snow between the tractor tracks had been scuffed away, leaving brown earth.

Ambrosio dropped the new post next to the old one. It felt like a tree-trunk against his back. The old fence was wobbly, the barbed wire was rusty and sagged, the posts were rotten and grey. Ambrosio was hardly any bigger than the post in his hands.

The farmer hoisted the sledgehammer onto his left shoulder. He held it down with the crook of his elbow while he spat on his hands. There was a dirty bandage round the finger where the nail had come loose. Knuchel was laughing. ‘We’re doing great. Not like the Boden farmer. This time last year he was doing the fencing with his Italian. Only they never seemed to make any headway. Ha! Farmer Boden was doing the hammering, and the Italian was holding the posts. Only they weren’t getting anywhere. All his swearing didn’t help, and he can swear. Farmer Boden, bloody hell, he can! The bloody posts were just refusing to go in the bloody ground. Then the Italian turned to the Boden farmer, and told him if he hit him on the head once more, he could hold his own bloody posts!’ Knuchel laughed, Ambrosio laughed too, and the hammer came down again, and again there was an echo of drumming from the little wood.

When the last of the posts had been knocked in, and Knuchel and Ambrosio were striding back up through the paddock to the farmyard to clean the shed and milk, the children and cats were already waiting for them.

Ambrosio turned round once more to look. He was now stepping less gingerly on Knuchel’s soil. Already he knew how cool the clover felt, and how soft a molehill could be when you dug around in it with the toe of your boot. He had begun to get his bearings: there was the farmyard, there was the meadow and there was the fence, behind were the arable fields, ploughed in rich furrows, and beyond them was another fence and bushes and a pasture that went from green, to greener, to greenest, and then shrubs, a whole hedgerow of them, and then another rise, a hilltop, then the treetops of a little wood, and behind that a hill, and behind that hill another hill, and behind the little wood a larger one, and behind that larger one, on the hill behi

nd it, an afforested area with proper mountains over it, and beyond them more hills and rises with brown patches in the woods, and more woods over these woods, forests, woods to prevent avalanches, pine woods at the foot of the screes, then suddenly, white and grey, plains of ice and snow and light and rock and sheer cliffs, the contours raw and black, ascending to peaks and domed summits and needle points, and above them only a little room left for the sky, and the clouds the same as the ones here over the farmyard, and Ambrosio turned back and breathed deeply.

In the paddock, the farmer too looked back on the pasture. ‘It’s going well,’ he said. ‘Soon we’ll be able to let them out. The whole lot. Before Whitsun, if everything goes well. Now let’s go!’ He walked past the chicken-run up to the byre door.

Inside, the cats sat down in the passage behind Bossy, and the children squeezed in beside Blösch. The calf was standing straddle-legged parallel to its mother, but facing the other way. As Blösch’s tongue was rubbing and cleaning round its anus, it was sucking at a teat.

‘It’ll have the scours,’ said Knuchel. ‘Drunk too much, the bloody bull calf has! The whole passage is shat up. That’s what you get when you leave them to themselves. Here, Hans, practice makes perfect, take a broom and clean up.’

‘And when can I give the calf a drink?’ asked Thérèse.

‘No, I want to do it,’ said Stini.

‘Not today, maybe tomorrow,’ was Knuchel’s answer.

Ambrosio fetched the wheelbarrow. Stini pointed at Stine and said, ‘That’s my cow.’ The farmer dug his fork into the straw and said, ‘Yes, that’s your cow,’ and to Ambrosio: ‘They were born on the same night. Almost within an hour of each other. What a business, I hardly dare think about it. By God, you weren’t sure if you should stay in the byre or in the bedroom.’ As he was speaking, he took a look behind every cow up and down the shed. ‘Ay, see, we don’t let our creatures shit in the village square, and they don’t piss in their water either. No, we put all that back in the soil – we’re not stupid!’

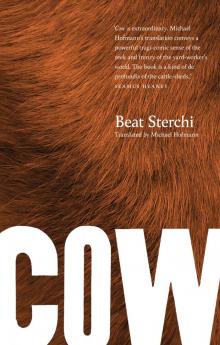

Cow

Cow